How to use campus design to nurture a culture of belonging

Brian W. Casey and Graham Wyatt discuss the importance of campus design and beauty in support of the student, faculty and staff experience

You may also like

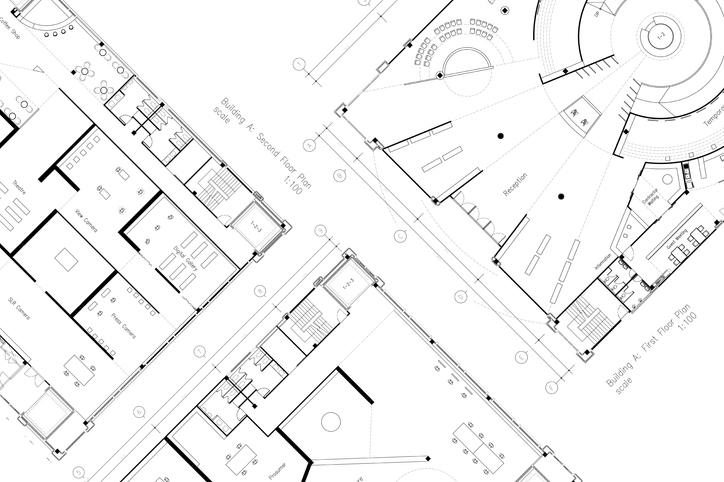

While carefully developed academic programmes and campus social activities are essential to a fulfilling on-campus student experience, campus design also plays an essential role in the life of the university. So how can the physical transformation of existing campuses rise to this challenge?

Expand from within

Campuses frequently expand around their edges for understandable reasons. Fringe sites are thought to be more available and less prone to opposition from campus stakeholders. Construction on these sites is perceived to be less disruptive.

However, growth-through-sprawl supersizes campuses, destroys pedestrian-friendly scale and reduces social cohesion. Sprawling campuses are often obliged to buy real estate, removing land from tax rolls and worsening town/gown relations.

Campus sprawl also isolates mutually supportive activities and disciplines. STEM buildings (often among a university’s newest disciplines and buildings) are often marginalised in campus-fringe locations remote from sites that support disciplinary diversity.

- How to select and monitor climate adaptations for universities

- Lessons learned from building a new university premises

- Creating ‘third spaces’ will revolutionise your campus

The compact campus cores that characterise some of the most attractive and socially engaging universities don’t happen by chance. They are planned carefully and nurtured patiently. Many campus planning initiatives can be improved significantly by the carefully considered insertion of a few new buildings.

Buildings and programmes that occupy these core sites should be placed in ways that define attractive and programmable outdoor spaces such as quadrangles, courtyards and campus walkways.

Additionally, adaptive re-use of existing buildings can tap the potential of a campus core. Old structures with good bones can effectively accommodate new functions in resource-efficient ways. These opportunities can create new homes for academic functions with updated instructional classrooms.

Improve campus connections and re-imagine residential spaces

Distance on campus should be measured in terms of the perception of distance, not in metres or minutes. Walking along 200 metres of landscaped campus walkway is immeasurably more inviting than 200 metres across a parking lot.

Indeed, many campuses are known as much for their signature walkways as their buildings: Locust Walk at Penn State, McCosh Walk at Princeton, the Long Walk at Kenyon and the recently reimagined Speedway at the University of Texas Austin – each of these is an important campus social integrator and a defining element in our campus mental map.

Proposed new walkways can combine landscape restoration with a direct and accessible pedestrian connection that connects two disparate areas of a campus – like with Colgate University’s upper campus, its academic heart and home for first-year and sophomore students, and its lower campus, home for the arts, athletics and junior and senior student residences, which are now connected by a new walkway through a natural ravine.

These types of pathways and physical connections can work well in tandem with a residential commons system to foster connections and a sense of belonging on campus. Residential colleges, houses and commons systems are becoming increasingly popular on campuses as a way to create smaller communities for students within the broader campus environment. Additionally, these systems help provide amenity parity across the student experience.

To optimise these systems for students, geographic coherence must be a top priority, creating a distinct space for individual commons to hone a sense of community but not in a way that isolates students from integrating into, and experiencing, the rest of the campus. Residential commons designs can be adapted in a way that provides developmentally appropriate independence.

For example, there might be first- and second-year residential commons prioritising predominantly twin rooms clustered in smaller social communities, each with shared bathrooms and lounges and faculty supervisors. Shared outdoor spaces such as quadrangles and courtyards can also act as natural community and social hubs for students in these commons to connect and congregate, as well as acting as literal, physical connectors between spaces.

For more senior students, residential commons can be designed as interconnected and cohesive campus villages with housing models more like apartment-style residences, providing developmentally appropriate independence served by shared studying centres and other amenities. This commons design balances community belonging with a sense of independence.

Through such campus designs, students can be welcomed into the school with an immediate sense of belonging in smaller communities where membership is extended to all, and experience a natural progression towards more independent living that is balanced with community and belonging.

Sustainability, beauty and campus identity

Environmental sustainability is key to campuses as they look to the future. A dozen or so universities in the nation have achieved carbon neutrality. But this does not have to be at the expense of the historic design or beauty that enriches campus identity.

New construction and renovations of existing buildings can honour architectural context while also being sustainable. Sustainability is not tethered to a specific architectural style but can be embedded into campuses of many types.

As campuses grow and evolve, their unique architectural characters can be honoured while still meeting contemporary needs. Many new buildings on historic campuses use period forms, proportions and materials yet are programmatically and technically modern, integrating energy-reducing features such as heat pump systems and triple-glazed windows. The most popular new buildings generally express a unique character.

Buildings can also serve as valuable learning tools, woven into a campus experience that educates and engages students. Jane Pinchin and Burke Hall residences at Colgate, for example, include building systems that allow students to track and manage their energy use.

Students and prospective students care about these issues, and they vote with their feet. We have all heard of a prospective student refusing to get out of their car based on a windshield-first impression of a campus.

Though much time is spent talking about campus buildings that “express the future”, few things can age faster than today’s idea of the future.

Let’s not shy away from talking about campus-making, architectural character, comfort and beauty. Though these might be at odds with the heroic architect model of campus design, they are essential issues for a campus community. Properly considered, they support and foster belonging among a diverse campus, provide a compellingly inviting vessel during the formative undergraduate years and inspire lifetime loyalty.

Brian W. Casey is president of Colgate University, US, and Graham Wyatt is a partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA).

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.