UK sixth-formers traipse up and down the country, at considerable expense and often with family or friends in tow, to attend university open days. They carefully consider each campus’ learning environment and student life offerings. When they get home, they pore over course evaluations and student outcomes data. They take the decision about which university is right for them very seriously.

And rightly so. After all, universities are more than just academic institutions. They are also vibrant hubs of social engagement, where intelligent young people can embrace the independence of adulthood and acquire a sense of intellectual and personal growth by interacting with a wide range of people and actively engaging in lectures, seminars and practicals.

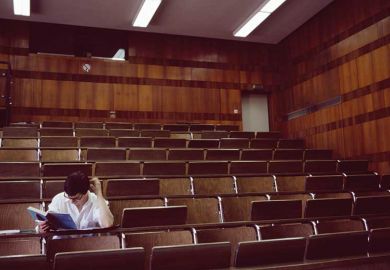

However, since the pandemic, students just haven’t been coming back to campus. Stories abound of lecturers confronting near-empty lecture halls.

One reason may be that we haven’t communicated the importance of physical interaction well enough to the post-Covid generation. Another is that we have been actively eliminating some of the smaller, departmental social and communal spaces in universities in the name of efficient use of space. And a third is the greater need for students to undertake paid work during the cost-of-living crisis.

But another major factor that could be inadvertently chipping away at this cornerstone of the university experience is the recent trend towards lecture capture.

The real-time recording of live lectures is motivated by a noble desire to enhance learning. It can also enhance self-reflection, support diverse learning styles and aid learning in a second language. It is popular with students, who claim that it reduces stress when they cannot attend lectures and helps them with exam revision.

However, a growing body of research suggests that these benefits are coming at the cost of the broader well-being of both students and staff. Recordings might offer the illusion of learning, but a troubling trend is emerging whereby students who rely heavily on them exhibit lower levels of critical thinking and deep understanding compared with those who actively participate in lectures.

There may be several reasons for this. One is that obsessively watching recorded lectures over and over is a poor substitute for doing the wider reading that develops students’ critical thought processes. Another is that lecture capture is associated with a decline in student-lecturer interaction and engagement. Students who do not physically attend lectures do not get to know their lecturers in person and, therefore, may feel uncomfortable engaging in class discussions and asking clarifying questions. Hence, they miss out on the opportunity to receive immediate feedback, hindering their comprehension of complex topics.

In turn, without active student engagement, lecturers lose the opportunity to actively adapt their teaching based on immediate feedback and emerging learning needs. And, with it, they are losing their sense of job enjoyment. Rather than the gratification of seeing the penny drop with their audiences, they are now spending too much time and energy worrying about the quality of lecture recordings and correcting wayward AI-generated subtitles – not to mention scratching their heads about what they can possibly write in a requested job reference for a student they have never even met.

Most frighteningly, students are no longer even engaging with each other in class. Their sense of belonging is apparently missing, which affects their academic achievements, their self-confidence and their motivation to study. Social learning theory emphasises the importance of human interaction, such as via collaborative problem-solving. The back-and-forth of ideas, the shared exploration of complex topics, the spontaneity of jokes and stories, that joyful lightbulb feeling when you grasp a point and share it with your peers: these are all casualties when students passively consume recorded lectures.

It is no surprise, then, that student loneliness and mental health issues are also on the rise. According to a recent government-commissioned survey, almost all UK students experience loneliness at university, while another survey found that half have mental health difficulties that negatively impact their university experience.

The benefits of flexibility and accessibility should not be dismissed, and we are all for the technological enhancement of learning. However, more careful reflection is urgently required about how lecture recordings are used. For example, research has shown that they are viewed most often during assessment and revision periods; one suggestion, therefore, would be to make recordings available only during these times – or only to support more carefully targeted individual needs.

We owe it to our students to ensure that our campuses remain hubs of intellectual exchange and personal development. Let’s pause lecture recording for now and put a stop to the student loneliness pandemic.

Treasa Kearney is senior lecturer in marketing and Liz Crolley is professor in management education at the University of Liverpool.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Let’s pause lecture recording and stop student loneliness

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login